In recent years central banks around the world have played increasingly active roles in directing the performance of their national economies and financial markets. Historically, the ability to control short term interest rates has influenced economic trends, with banks enacting low interest rate policies when growth is sluggish and raising rates when inflation becomes a concern. After the financial crisis of 2008, however, the US Federal Reserve encountered a problem: with interest rates already effectively reduced to 0%, the Fed had lost its ability to stimulate growth by changing rate policy.

Printing Money

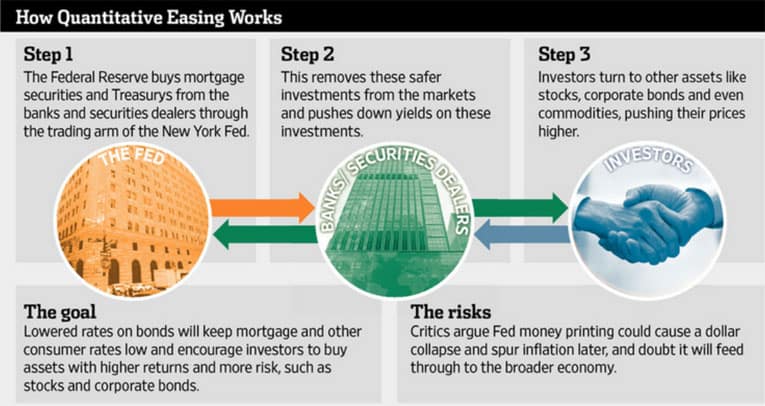

Because of this, in 2009 the Fed turned to its next option, the now well-publicised Quantitative Easing (QE) program. Put simply, QE is enacted when a central bank creates money, usually to buy bonds from banking institutions, which will then be able to approve more consumer loans with the extra cash.

Theory vs Practice

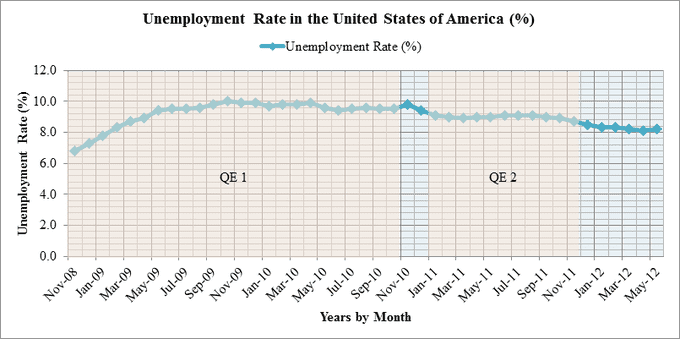

Unfortunately the real world economy doesn’t always obey the rules set by economic theory and when banks lack the confidence required to make increases in consumer lending, the enhanced money supply will not create the growth engine that was originally intended. While high unemployment rates and slow growth persisted, the Fed decided to follow its first stimulus proposal (QE1,valued at $1.25 trillion), with a second round in 2010 (valued at $600 million in short term bond buys).

With both QE programs failing however to prevent weakness in economic data, a third round of QE was announced (valued at $85 billion in monthly mortgage-backed securities purchases), generating sharp criticism from many market analysts. Most of this criticism has been directed at the fact that this third round will be open-ended which essentially means that the Fed can continue pumping money into the financial system as long as it sees fit (and therefore became known as “QE Unlimited”).

Critics Angered

There is a growing level of criticism against this approach by the Fed, and those critics argue:

QE helps banking institutions more than the economy as a whole, because banks can improve balance sheets and keep the additional money, rather than lending it out;

the domestic currency weakens relative to foreign currencies;

greater money supply can create inflation that cannot be contained later;

artificially low interest rates and increased cash supply will create asset price bubbles where more money is chasing a decreased supply of products.

It should be noted that commodity prices saw sharp rises after the QE programs began.

So What Is the Reality?

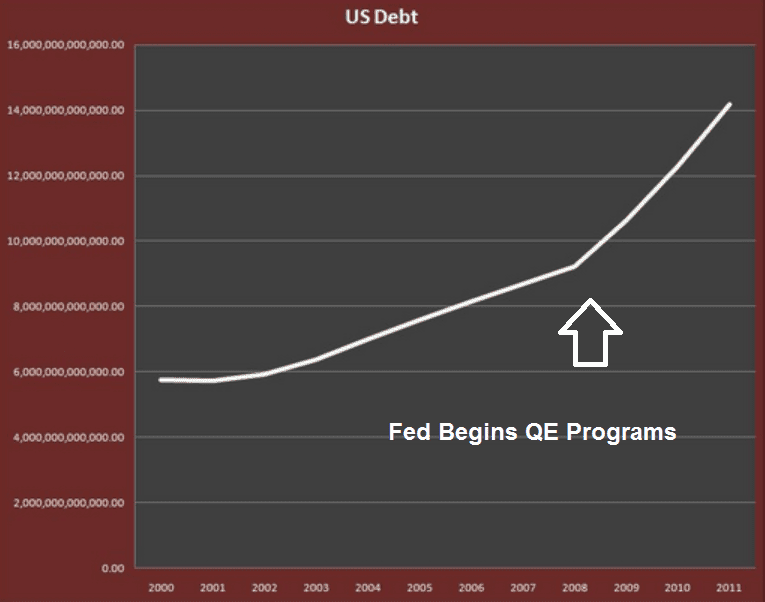

At the same time, government debt in the US experienced similar upward trends, showing a 250% increase in the last 10 years. Since interest expense has not increased at the same rate, low interest rates are allowing the new debt creation to approach dangerous levels. The main risk is that if interest rates move higher in the future, the US could find major difficulties in repaying its government debt in a timely fashion.

Higher inflation can help with long term debt repayments, but in an environment where interest rates are rising, it becomes difficult to rollover short term debt. The chart below shows large increases in government debt in the years following the Fed’s QE programs, as debt (expressed as a percentage of GDP) rose from 67.2% in 2008 to 103% in 2012.

Making QE Work Better

Since the Fed has left its third program open-ended, one possible route to making QE3 (“‘Unlimited”‘) work better could be if the Fed were to set more specific targets. For example, if the asset buying continued until either inflation starts to become unmanageable (say, rising above 3%) or until the unemployment rate drops to 6%.

A strategy focused in this way could help to improve expectations and increase consumer confidence relative to the way the economy is progressing. Both of these factors could prove to be instrumental in driving economic growth and the overall success rate of the third round of QE. The unfortunate fact, however, is that there is not much historical precedent for these types of policies, making it difficult to predict how these strategies will affect the economy in the longer term.

When looking at the unsuccessful outcome of the practice in Japan in the early 2000s (which was meant to control the country’s domestic inflation problems), a possible outcome can be seen. While QE programs do tend to be associated with quantifiable declines in longer-term interest rates, the balance of evidence suggests that weaker Japanese banks were aided by these programs and that greater risk-tolerance was encouraged in the wider market.

These outcomes are dangerous in that artificial attempts to strengthen the performance of weak and deficient banks has shown that quantitative easing may have the unintended impact of delaying more structural reforms that would have allowed more stable banks (and other companies) to thrive.

Where To From Here?

The Fed has very firmly committed to QE programs, and while many have been critical of the apparent failings of QE1 and QE2 to achieve any meaningful results other than driving up government debt, the fact remains the Fed is now printing money on an unlimited basis without signaling when this will end.

If history is any predictor of the future, then this is unlikely to have a very happy ending. The key issue for investors will to be keep a sharp eye out for signs of inflation and asset bubbles in the US economy as a consequence of the record low interest rates and increasing cash supply.

Finally, the sustainability of the QE programs will only be determined once a solution is found to reign in existing US government debt levels, which are increasing as the QE programs expand. The newly re-elected President will need to solve this debt problem, with a package agreeable to both the Republican controlled House of Representatives and Democrat controlled Senate.

With history against it, record government debt, and a divided Congress, QE Unlimited may be the only option available to the Fed, but it is a potentially disastrous one. Even Buzz Lightyear would start to loose some of his unwavering confidence at this point… “‘to infinity and beyond!”‘.