Monetary policy makers looking to protect Australia’s 21 consecutive years of recession-free economic growth have faced some significant obstacles in the last decade, with many analysts now suggesting that the central bank will need to reduce interest rates to all-time lows in order to keep that streak going. But with the economic slowdown in China deflating the prices Australia’s resource exporters are able to command for their materials, many miners have been forced to scale back more ambitious plans for investment and expansion.

Evidence of these changes can be seen in Australia’s Trade Deficit data reported in August, which showed its weakest numbers in three years. Developments like these have led to analyst criticism of the Australian government’s ability to properly address the needs of a slowing economy, rather than simply throwing finite resources at the problem in an effort to create some sense of short term stability.

A Look at the Long Term Trends: 2000-2012

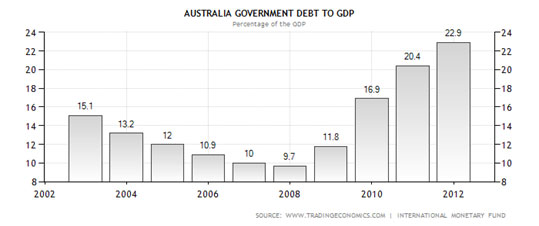

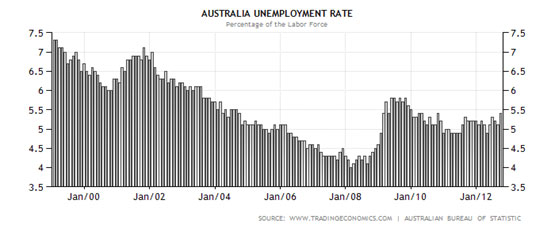

When looking at developments before and after the financial crisis of 2008, a somewhat startling picture emerges, as government debt (relative to GDP) has more than doubled the levels seen before the crisis, unemployment has passed the 5% mark, and quarterly growth on a national level has slowed to the tepid pace of 0.6% in the latest readings.

Growing Skepticism of Policy Direction

Both the government and the nation’s central bank maintain their growth forecasts of 3% over the next few years, but any surprise declines in investment that follow the mining splurge could cause consecutive quarters of contraction (meeting the conditions of a recession). RBA Governor Stevens has already made public comments suggesting that resource investments have likely reached a peak, making it essential for other components of demand (such as home building, manufacturing, tourism,or retail) to start gaining traction in order to maintain financial stability on a national level.

Thus far however, there is very little evidence to suggest that the RBA’s current policy direction is having a substantive impact. The glacial progress in areas like mortgage credit and new home sales is indicative of the broader picture in consumer borrowing which has actually retreated with Australians electing to keep their money in banks rather than investing in property or in equity markets. Since the financial crisis of 2008, bank deposits have risen by nearly 60%, while household debt remains historically elevated (at roughly 150% of disposable income).

Implications of a Potential Recession

Since the mining industry has been the primary driver of the Australian economy for more than a decade, any stalling here could have substantial implications for the rest of the country’s financial prospects. It can be argued that hiring in this industry has been the main reason unemployment has held below 5% in recent years.

But once mines and liquefied natural gas are constructed, companies can start to lay-off workers (as fewer employees are needed to run the essential operations). According to the estimates of one central bank economist, four times as many people are needed during the construction periods for iron ore mines (when compared to the operational digging periods), so any material declines in the origination of these projects could have a significant impact on wage and employment growth in the coming years.

Given that quarterly GDP figures are already hovering very close to contractionary (recessionary) conditions, there is not much room for policymakers to cushion the effects of any major transition toward an economic policy that is more self-reliant and based on domestic consumption. Of course, a balanced policy response will be a requirement in order to hold off downside contractions in quarterly GDP and create a sustainable post-2008 economic recovery.